From Food Pyramid to Plate and Back Again: Three Theories of Behavior Change

With the launch of the new USDA food pyramid last week, we went back to look at how federal dietary guidance has evolved over the past three decades.

What we found: three images that represent three fundamentally different theories of how to change what people eat.

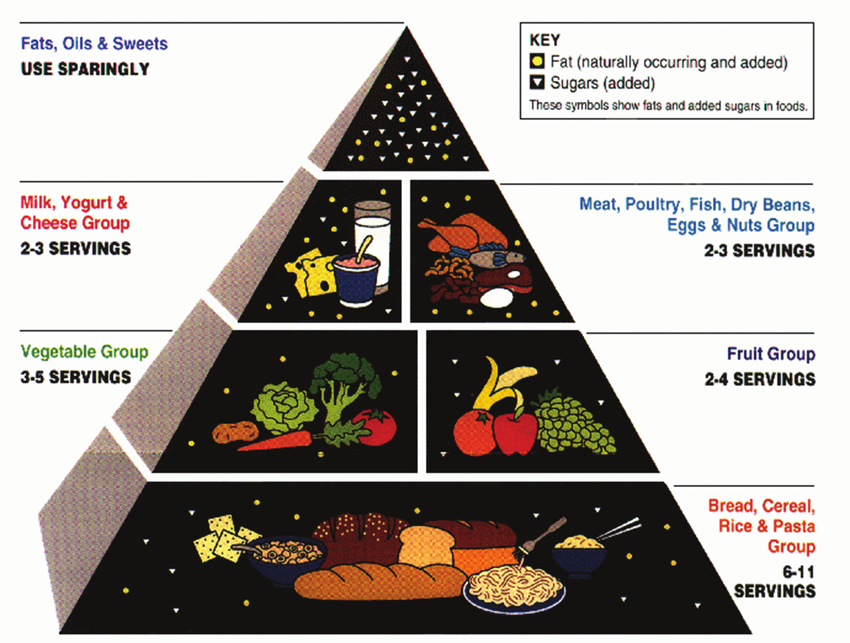

1992: The Food Pyramid

Abstract shapes. Bread at the base, fats at the top. Categories and quantities arranged in a hierarchy.

The design required interpretation. You looked at the pyramid, understood the ranking, then had to translate that into what goes on your plate tonight. It was a reference document, useful if you studied it, but disconnected from the moment of decision.

The underlying assumption: the barrier to healthy eating is knowledge. People don't know what to eat. Give them the right information, organized clearly, and they'll make better choices.

This is education as intervention. Inform people, and behavior follows.

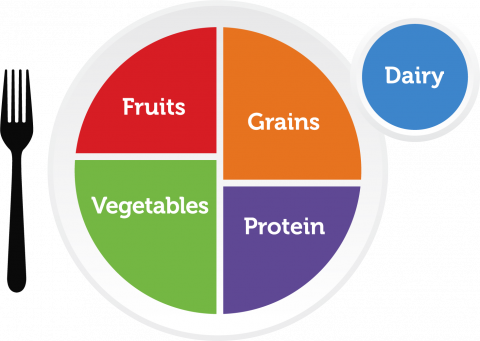

2011: MyPlate

A plate. Half fruits and vegetables, the rest divided between grains and protein. Dairy on the side.

The USDA moved away from the pyramid specifically because it proved difficult for people to interpret. MyPlate was the corrective: a form that matched the context of use. You're already eating on a plate. Here's how to fill it. No decoding required.

The underlying assumption: people generally know what's healthy. The barrier is friction. Translating abstract guidance into actual meals takes cognitive effort, and that effort happens at the worst possible moment, when you're hungry, busy, or deciding what to cook.

MyPlate reduced the distance between the information and the behavior. The visual was the behavior.

This is environmental restructuring as intervention. Make the behavior easier to execute by fitting the guidance into the existing context.

2026: The New Food Pyramid

Back to a pyramid, inverted this time, with protein at the top and grains at the base. But the real shift is in the imagery.

High-definition salmon that looks like it just came off the grill. Cracked eggs. Frozen peas in a bag, canned tuna, food in recognizable grocery store form. Photos over illustrations.

Three words instead of a framework: "Eat Real Food."

The design choice matters. Illustrations are processed cognitively. You interpret them. Photos land in desire. They trigger wanting before thinking.

The underlying assumption: people know what's healthy. They can figure out how to do it. The barrier is that they don't want to. The healthy thing isn't the attractive thing.

This is motivation as intervention. Reshape what people desire, and behavior follows.

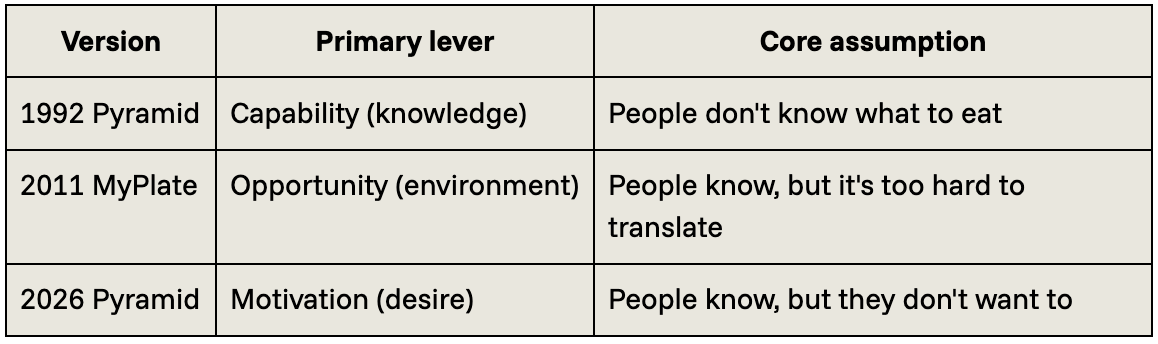

Three Levers

Behavioral design frameworks like COM-B suggest that for any behavior to happen, three components need to be in place:

Capability: Do people have the knowledge and skills?

Opportunity: Does their environment make it easy?

Motivation: Do they want to do it?

When a behavior isn't happening, at least one of these is weak. The job of intervention design is to diagnose which barrier is actually present, then target that.

What's interesting about the food pyramid evolution is that each version represents a different diagnosis:

If you get the diagnosis wrong, the intervention fails. You can educate people endlessly, but if the real barrier is that healthy food is inconvenient or unappealing, information alone won't move behavior.

Designing for Scale

All three barriers are real, and they show up differently across populations. But behavioral design research consistently points to one principle: opportunity-based interventions tend to carry more weight at scale. When you reduce friction or change the environment, you shift the default for everyone, not just those with the knowledge or motivation to act.

The 1992 pyramid trusted that knowledge drives behavior. MyPlate trusted that reducing friction would be enough. The new pyramid trusts that if you can change what people want, the rest will follow.

Each bet has merit. But if you're designing for population-level impact, the question isn't just what barrier exists. It's which intervention reaches people who aren't already looking for guidance.

MyPlate didn't ask anyone to want food differently. It just made the behavior easier to see. There's something in that.